Financial master or financial disaster?

COLUMBIA, Mo 03/31/15 (Feature) -- "Dear Wally," attorney Jonathan Browning begins. "I am sending this letter to you as the attorney for Jerry D. Kennett, a guarantor of the above-referenced loan," for $1.3 million....

Premier Bank, the letter continues, "is declaring default due to non-payment of amounts owed...and failure to comply with Security Agreements...."

Dated October 6, 2010, the letter asks Columbia attorney Wally Bley to "discuss this matter with your client, Dr. Kennett...." so that Premier and Kennett can "resolve this matter in an amicable fashion."

Two months later, Premier Bank filed suit against Kennett, the surviving owner of "Air Charters and Sales, LLC," a venture Kennett formed with deceased developer Jose Lindner, whose Columbia empire collapsed in bankruptcy.

Toppled by the housing bust, Premier eventually collapsed too, leaving Kennett -- a 2015 candidate for the Boone Hospital Board of Trustees -- to face the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in Boone County and US District Courts.

It is Kennett's latest high-profile financial disaster, which he, his lenders -- and taxpayers who pick up the tab when banks fail -- might have avoided, had only Dr. Kennett -- a cardiologist -- read The Physician's Guide to Investing, by Robert Doroghazi, M.D.

A fellow heart doctor, Doroghazi is Kennett's opponent in the Boone Hospital Board race. Ironically, his advice -- Don't be "The Mark"; "Invest in what you know"; "The Malevolence of Debt" -- reads like a road map around the financial pitfalls Kennett has been falling into for the better part of two decades.

Masters and disasters

The Hospital Board campaign has focused on financial acumen since Doroghazi jumped in.

"I believe my financial and money management skills are as strong or stronger than anyone who is considering a run," Doroghazi told the Columbia Daily Tribune.

He wants better terms from BJC Healthcare -- the hospital's long-time lessor.

And he wants the Boone County Commission's hands out of the $2.3 million pie BJC annually pays to lease Boone Hospital. That money, Doroghazi maintains, should stay with the hospital to hire nurses rather than flowing into County coffers to fix roads.

Kennett, meanwhile, remains mired in money messes, his latest involving an employment lawsuit filed by fellow cardiologist Sanjeev Ravipudi, M.D.

Alleging "secret meetings," back stabbing, and double dealing, Ravipudi sued his employers -- Kennett and Missouri Cardiovascular Specialists (MCS) -- in 2014.

The lawsuit was settled in January for undisclosed terms. Kennett did not respond to questions about it -- or the other topics in this story.

Give 'em what FER

The Financial Misadventures of Jerry D. Kennett started around 1992, when he got involved with a convicted felon named Floyd E. Riley.

From Moberly, Riley was becoming notorious for financial finagling. A Missouri state pension plan known as MOSERS invested $1.6 million in a Riley scheme to process catfish, losing it all in a 1990 bankruptcy.

Two years later, Riley was indicted on 18 counts of conspiracy to commit bank fraud, after drawing up phony promissory notes for a company known as FER-Co Fabricators (the FER his initials).

Kennett partnered with Riley in a subsequent venture, FER-Tech Environmental. Riley had taken FerTech public "just five months after pleading guilty to felony counts of wire fraud, and two years after emerging from personal bankruptcy," a St. Louis Post-Dispatch story explains.FerTech Environmental failed in 1995, after defaulting on a $2 million loan.

"FerTech -- the most recent venture of convicted felon Floyd E. Riley -- owes millions to NationsBank of Texas, various suppliers, and its employees," the Post-Dispatch reported. "The three major investors in FerTech -- Riley and two of his closest associates, G. Allen Mebane and Columbia, Mo. cardiologist Jerry D. Kennett -- declined to return phone calls."

"Who Can You Trust?" is the title of Chapter 17 in Doroghazi's guide to investing. Rule #4: "Never invest with anyone with a criminal record or any history of shady deals."

"Complicated transaction"

"Fertech operated mobile systems to clean contaminated soil and oil spills," the Post-Dispatch explains. But what did Dr. Kennett know about cleaning contaminated soil, a regulation-laden, equipment-intensive enterprise?

"Invest in what you know," Doroghazi advises in Chapter 8 of his book. "Invest where you already are an expert, i.e. medicine."

Other Doroghazi maxims include avoiding debt and embracing simplicity.

But "Kennett's initial investment in FerTech was a complicated transaction," the Columbia Daily Tribune reported.

Rather than putting up cash, Kennett signed promissory notes pledging $500,000 to FerTech in exchange for stock.

"To raise the needed cash, FerTech sold Kennett's notes to Columbia businessmen for less than their face value," the Trib story continues. "Kennett now owed the $500,000 to the businessmen, not FERtech. The whole thing worked -- for a while."

It stopped working after FerTech failed to finish a soil cleanup job at a Texas airport. The Columbia businessmen -- developer Stan Kroenke and Harpo's owner Dennis Harper -- sued, seeking hundreds of thousands of dollars from the loan guarantors.

At that point, Kennett owned 17% of FerTech, Mebane 32%, and Riley 51%.

Optimistic but unrealistic, "Kennett sought to save FerTech. 'I think there will be an infusion of capital, and the company will continue to operate,'" he told the Post-Dispatch.

Riley later pled guilty to more felonies, including money laundering, transporting stolen property, and wire fraud. He was sentenced to 21 months in prison in 2004.

Kennett's next venture was a healthcare education company that filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in 2006.Graphic failure

By all accounts, Jerry Kennett is one of the nation's finest cardiologists, a physician any patient would be wise to trust with his or her heart.

Named a Master of the American College of Cardiology in 2012 -- the group's highest honor -- "Dr. Kennett was caring, supportive, and thorough," patient family member Kristie Wilson writes in a campaign testimonial.Boone County voters, however, are looking for more than a good doctor on their publicly-owned county hospital's board of trustees.

They want someone they can trust with publicly-held capital, a job Kennett did not handle well as a company director; #1 shareholder; and #1 creditor of Graphic Education Corporation (GEC).

A Columbia-based provider of online and software healthcare education tools, GEC sought Chapter 7 bankruptcy -- total liquidation -- in July 2006.

US Bankruptcy Court paperwork lists 29 shareholders, including former Columbia Mayor Darwin Hindman and Fourth Ward Councilman Ian Thomas.

It also lists roughly $3.6 million owed to multiple creditors, including Callaway Bank; Columbia resident C. David Duffy; Mizzou's Office of Research; and Dr. Kennett.

The cardiologist's $2.9 million "unsecured" claim against GEC made him both its largest creditor -- and largest shareholder, with 5,513,573 shares of stock, which the bankruptcy rendered worthless. Company founder Jon Rosen held the next highest number of shares, at 1,504,052.

Councilman Thomas escaped relatively unbruised, with only 3,732 shares.

The Mark

"He was a smooth talker, I can tell you that," Columbia land owner W.B. Smith told the Columbia Daily Tribune about Jose Lindner.

Larger-than-life, Lindner was as well known for his successful projects -- the Forum and Nifong Shopping Centers, Broadway Shoppes -- as he became for the spectacular downfall of a real estate and investment empire unusually dependent on high-salaried physicians like Kennett."In 2002, Lindner’s heart doctor, Jerry Kennett, co-signed a $1.65 million loan from Citizens Bank & Trust," the Tribune reported. Lindner died in 2010 and the bank went after his estate, joining $40 million in other claims.

Likewise, Premier Bank and the FDIC sued Kennett in 2010 as the owner of Air Charters and Sales -- a partnership with Lindner -- and guarantor of a $1.3 million loan.

In the language of Doroghazi's investment advisory, Kennett and the other physicians who partnered with Lindner may have been "easy marks", i.e. naive targets for an unscrupulous type seeking easy money.

"You may be a hard-working, superbly-trained, absolutely brilliant physician, but many people consider you "The Mark," Doroghazi explains in Chapter 4 of his book.The Dark Side

Kennett's misadventures with the FDIC started over money Premier Bank loaned to "purchase equipment for aircraft," the guaranty he signed explains.

Lindner and Kennett pledged a 1983 Mitsubishi MU-300 aircraft as collateral.

As personal guarantor, Kennett "is liable for the amounts due and unpaid," the FDIC/Premier lawsuit claims, alleging Breach of Security Agreement, Breach of Note, and Breach of Guaranty. "The defendants failed and refused to make said payments, and further failed to surrender the Collateral."

Kennett admitted some of the claims but denied the most serious charges, including that he owed the money. The original loan, he explained in court filings, "was substantially and significantly modified" to such a degree that it "terminated or extinguished any prior guarantee" Kennett gave to the bank.

By failing to communicate with him, Premier Bank had also breached its agreements and duties, Kennett maintained.

"Debt is the financial equivalent of the dark side of the Force," Doroghazi writes in Chapter 18 of his investment guide, aptly titled "The Malevolence of Debt." "It is like the Song of the Sirens, ready to entice the unwary onto the rocks of financial destruction."

Those rocks include courts, where Kennett's misadventures with Jose Lindner ran aground.The Firm

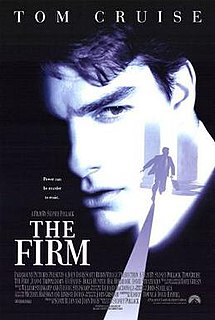

The Boone County court case of Sanjeev Ravipudi, M.D. vs. Missouri Cardiovascular Specialists (MCS) and Jerry Kennett, M.D. reads like a movie script from the early days of Tom Cruise's career, back when he was the earnest young attorney in The Firm and A Few Good Men.

Earnest, young -- and about to get a hard lesson in high-level office politics.

Within six months of his employment at MCS in 2002, Ravipudi was already earning bonuses. Eighteen months later, the firm's partners, "impressed by his clinical and procedural competence as well as his economic performance," made Ravipudi a partner earlier than most.

Things started going awry in 2007, when Ravipudi objected to a change in the partners' "compensation formula" that benefited Kennett at the expense of other partners.

Ravipudi's objections "hindered the swift ratification of the new compensation formula and other MCS modifications favorable to Kennett (such as avoiding weekend and overnight call coverage)," court documents explain. "This angered Dr. Kennett."Boone Hospital's new professional services agreement with MCS covered all its partners by 2014. Now Chief Medical Officer (CMO) at the hospital, Kennett launched an investigation of Ravipudi for breaching certain hospital protocols. The younger cardiologist was "not allowed to know the names of witnesses against him" nor "be present during interviews and testimony."

Conflict of interest concerns prompted Ravipudi to demand Kennett recuse himself from the proceedings, but he did not. The hospital's Medical Executive Committee promptly denied Ravipudi's request for a "fair hearing" under Boone Hospital's Medical Staff Bylaws, the suit claims.Ravipudi appealed the ruling and went back to his 12-hour workdays, trying to maintain his partnership at MCS, where a "secret meeting of the partnership" was held with "Dr. Kennett leading the effort" to terminate him.

Without notice, nor Ravipudi's knowledge or presence, the meeting violated the firm's partnership agreement, Ravipudi claimed, backing up his dispute with multiple citations from the agreement itself. Like Cruise's character Mitch McDeere in The Firm, Ravipudi -- with his objections and appeals -- had become an annoyance, a problem even, the suit claims.

Dr. Kennett wanted him out.Trust and Trustee

Settled in January, presumably with Ravipudi's departure from the firm and loss of his livelihood, Ravipudi v. Kennett is another ironic reminder of why not only physicians, but everyone, should invest wisely, carefully -- and skeptically.

"The training of a physician involves trust," Doroghazi explains. To provide the best care, physiciansmust trust what their patients -- and colleagues -- tell them.

"But in the business and legal world" Doroghazi warns, "such unquestioning trust is a formula for disaster."

So too in the political world, where "trust" is the heart of the word "Trustee", a job two Columbia heart doctors are vying for with this question: Whom will you trust, April 7?

-- Mike Martin

Sidebar

Mobile Menu

The Columbia Heart Beat

COLUMBIA, MISSOURI'S ALL-DIGITAL, ALTERNATIVE NEWS SOURCE

The Columbia Heart Beat

COLUMBIA, MISSOURI'S ALL-DIGITAL, ALTERNATIVE NEWS SOURCE

23

Sat, Nov