Do good -- but do no harm

COLUMBIA, Mo 6/17/15 (Analysis) -- Neighbors near a proposed, city-sponsored "homeless drop-in center" on North Eighth Street in Columbia are voicing concerns about the potential for crime, loss of privacy, and other problems.

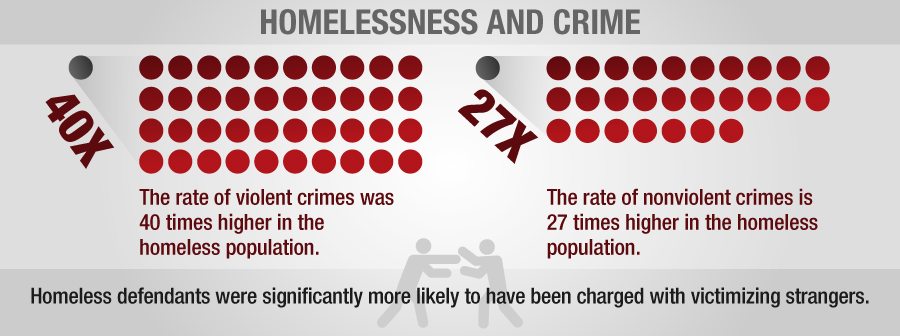

If recent history is any guide, their concerns are justified.

A homeless drop-in center at 702 Wilkes Blvd. -- a church roughly one long block from the 8th Street location -- has been plagued with assaults, harassment, theft, peace disturbances, trespassing, and arrest warrants since it opened last April, according to Columbia police dispatch logs.

Neighbors have also complained -- about petty theft, drug dealing, fighting, and public intoxication. With nowhere else to go, often after a foot or bike trek in bad weather, homeless persons wait on nearby streets, sidewalks, parking lots, or yards until -- and after -- meals or shower time.

"I've seen people go right from the church and buy drugs," a nearby female resident said. "I've had them scream at me. One guy even tried to hit me."

This writer -- a homeowner in the neighborhood for 13 years -- witnessed a loud argument next to the church about a month ago, among women -- two of them clearly intoxicated -- waiting for a meal.A comparison with the well-known homeless shelter St. Francis House -- at nearby 901 Rangeline Rd. -- suggests part of the problem may lie with the drop-in center model.

The number of police dispatch calls to the church between 6/15/14 and 6/15/15: 106.

The number of police dispatch calls to St. Francis House during the same period: 0.

As short-term alternatives to long-term shelter, drop-in centers are less able -- and less likely -- to offer the care and expertise to effectively deal with long-term homelesness and its causes -- mental illness, offender behaviors, and substance abuse/addiction chief among them.

An application from 8th Street drop-in center organizers seeking public money is heavy on hope but light on details. Comparing it with this paper from Ohio State University (OSU) researchers on "How to open and sustain a drop in center for homeless youth" reveals gaps which include neighborhood consideration.

In their application, Eighth Street drop-in center organizers push neighborhood concerns -- "parking, public safety, property values, pedestrian access, traffic flow, noise, land use compatibility" -- into the future ("we'll address that stuff after we get our grant money"). They emphasize "rezoning" -- a major land use change not necessarily compatible with existing residences -- will be necessary for their location, a 21,000 square foot vacant lot City Hall purchased for $80,000.

The OSU researchers, on the other hand, insist that to be successful, a homeless drop in center must be part of the neighborhood rather than superimposed over it.

"Accessibility and capability need to be at the core of the drop in center on a number of different levels," the researchers note. "Accessibility is tied to not only location, but...the level of 'buy in' the people who inhabit the area have for that location. Drop in centers should not change the landscape of the community."Resident impacts are even more pronounced in low-income neighborhoods struggling with their own social and economic issues. Protests in 2013 over a homeless shelter in a NYC neighborhood -- considered one of the city's poorest -- illustrate this heightened impact.

Low-income neighbors may have legitimate worries, but little political clout to realize honest consideration early in the process. Their neighborhoods, likewise, aren't always the best places for high-impact social work, but default locations chosen to avoid NIMBY worries in higher-income areas.

It's hard to imagine a homeless drop-in center in The Highlands or the Old Southwest; even harder to imagine the multiple shelters and halfway houses that currently call the 8th Street area -- North Central Columbia -- home.

No one understood the causes and complications of homelessness -- and the boots-on-the-ground strategies needed to combat it -- better than Washington, DC activist Mitch Snyder, with whom this writer worked as a young man.

Unapologetically troubled, Mitch was also profoundly passionate about his cause. He believed only long-term approaches could resolve homelessness, living, eating, and breathing that philosophy. It was a level of commitment difficult to imagine a homeless drop-in center replicating.

Society needs to address poverty, but with an eye toward ending it, especially when public tax dollars are involved. Anything less can become a band-aid that perpetuates problems rather than healing them, ultimately doing more harm than good.

RELATED:

Homeless drop-in center appeals for city funding

Social services agencies hear city's plans for homeless drop-in center

-- Mike Martin

Sidebar

Mobile Menu

The Columbia Heart Beat

COLUMBIA, MISSOURI'S ALL-DIGITAL, ALTERNATIVE NEWS SOURCE

The Columbia Heart Beat

COLUMBIA, MISSOURI'S ALL-DIGITAL, ALTERNATIVE NEWS SOURCE

02

Mon, Mar